4 min read

Every Perspective has a Story: Listen for It

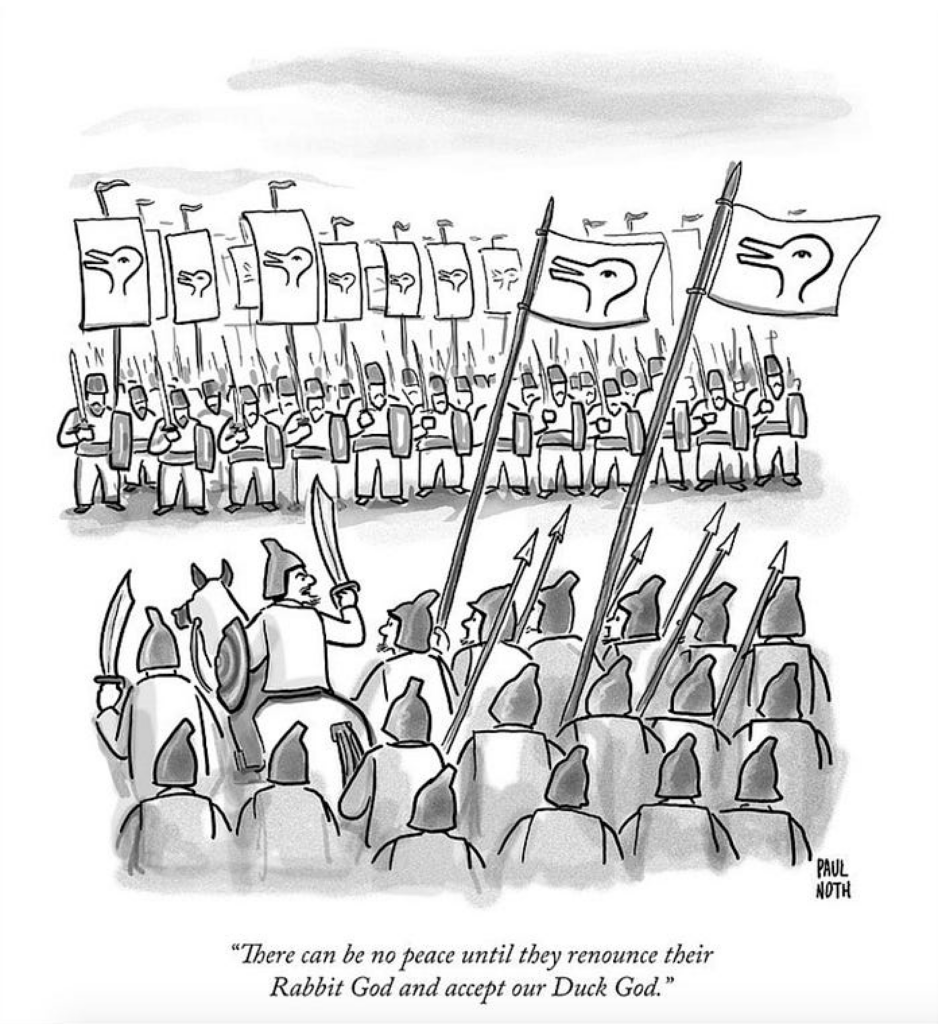

“An Army Lines Up For Battle” by Paul Noth. The New Yorker, December 1, 2014.

Article originally published on Medium in 2020 and slightly revised when posting here in 2025.

If everything around us seems new and different, let’s make the ways in which we listen new and different, too.

Unprecedented times demand the cultivation of a beginner’s mind. Let’s listen to people as if everything we are hearing from them is new. As if we are hearing what they have to say for the first time. We are, after all, hearing it for the first time in this entirely new context.

Consider: why would you be listening in the first place if you know exactly what they are going to say?

You may have previously tried to be a better listener. Perhaps busyness, distraction, or anxiety got in the way of your skill-building. Behavior change is hard. But from the pandemic to unprecedented political events, turbulent times offer a context that can habitualize our being better listeners.

Of course, our current context also includes rampant distrust and anger, stoked by increasing inequity and weaponized media. I’m not claiming economic and political divides will be cured by everyone being better listeners. We will continue to disagree with others. But better listening will likely take things down a notch. Being heard and hearing others can diffuse anger, reduce defensiveness, and cultivate compassion.

During the pandemic, I facilitated a program in listening for professional communicators. I opened by asking, Over the course of a week, how many minutes of high-quality listening do you receive? And, How often do you get to listen simply to understand perspective (not for interpretation or analysis)? Quickly — and shockingly — the majority of participants admitted they themselves fully listened to another person for only 10 minutes a week. After a focused and intentional paired exercise, the participants announced their surprising realization: they had to be listened to before they could listen to others. Once they themselves felt heard, they could hear others with a compelling openness.

Here’s how those leaders quickly learned to listen better and hear more:

First, they set their intent. Both partners knew they would be refraining from assumption and listening to each other with openness, eagerness, and a fresh mind. We had done a couple of exercises to cultivate this sense of listening with a beginner’s mind. Then, I asked them to “share a story about a time you felt truly listened to” or “about a time that, despite your best efforts, you were unheard.”

You too can bring a beginner’s mind to any conversation. Ask yourself, as Krista Tippet asks, “When the conversation starts, are you really ready to be surprised?” You can commit to learning at least one thing from the person with whom you are speaking. Extend a proverbial welcome mat, with inquiries so open the person feels they will indeed be heard. Allow people to teach you and they will likely share their expertise. And we are all experts on our own lives.

In the run up to the 2016 U.S. presidential election, my friend Melissa volunteered as a “deep canvasser” in an effort to increase voter turnout. This meant rather than asking closed-ended, yes or no questions, Melissa was attempting to engage people in longer phone conversations. She wanted people to feel heard, in the hopes they would better engage with democracy and turn out to vote.

Melissa set her intent to listen without judgement or assumption. Even when confronted with anger, she remained intent on practicing listening with an open mind. In one thirty-minute call, a gentleman explained he was often picked on as the youngest of six children and didn’t have much of a voice in his family. Donald Trump, he explained, may be a bully, but the president was his bully. By listening without judgement, Melissa validated his experience, demonstrated interest, and provided him with respect. The call ended with increased understanding and compassion. The gentleman, Melissa believes, felt heard.

Melissa, and the participants in my program, transcended hearing opinion and generalized hypotheticals by setting their intent for better listening and cultivating a beginner’s mind — and by asking for and listening to stories. By asking about the person’s experience, they heard the truth of the lived experience of the person with whom they were speaking. Since what the other person was saying was coming from their unique perspective and experience, everything they heard was actually new.

Likely, you and the person with whom you are speaking do share some perspective. By hearing their story, you are more likely to hear things that relate to your own experiences, and thus you are more likely to understand the meaning behind what you are hearing.

But there is always unique perspective. People’s stories start from different points of view, from different points of knowing. No one is seeing exactly what you see. None of us brings the exact same context and content to any situation. Not even our family members, best friends since childhood, or longtime spouses. Remind yourself you know only what something means to you. Let the other person tell you what something means to them, in their own terms. Your knowledge and understanding of the color pink, for example, may be very different than mine.

Like Melissa, you can ask people about the experiences that gave them that perspective. You can ask them to reflect on how the experiences they’ve had have contributed to the way they now see the issue. Participatory narrative expert Cynthia Kurtz reminds us that often people once felt differently. Reflecting on that shift provides an opening for them to relate to others who feel the same.

Asking for stories requires a shift from closed-ended to open-ended inquiry. It is the difference between, “How was your weekend?” and “Tell me about your weekend.” Between “How are you?” and “Tell me about what you’ve been up to.” My husband Tom is still marveling at his realization in response to a question he was asked one Summer: “What is something you did during the pandemic you never expected to do?” [Tom’s answer is that we discovered the joys of frozen pizza.]

There’s a benefit to asking for a story about learning or doing something new: most of what we know, we have learned from others. So opening up this line of thinking can remind both you and the person with whom you are speaking that we are all learners and teachers and we can all share information. And that we all know different things. Not a bad frame for starting out in conversation. Or for reminding yourself now is the perfect time to listen for the new, for what we don’t know.